by Delphine

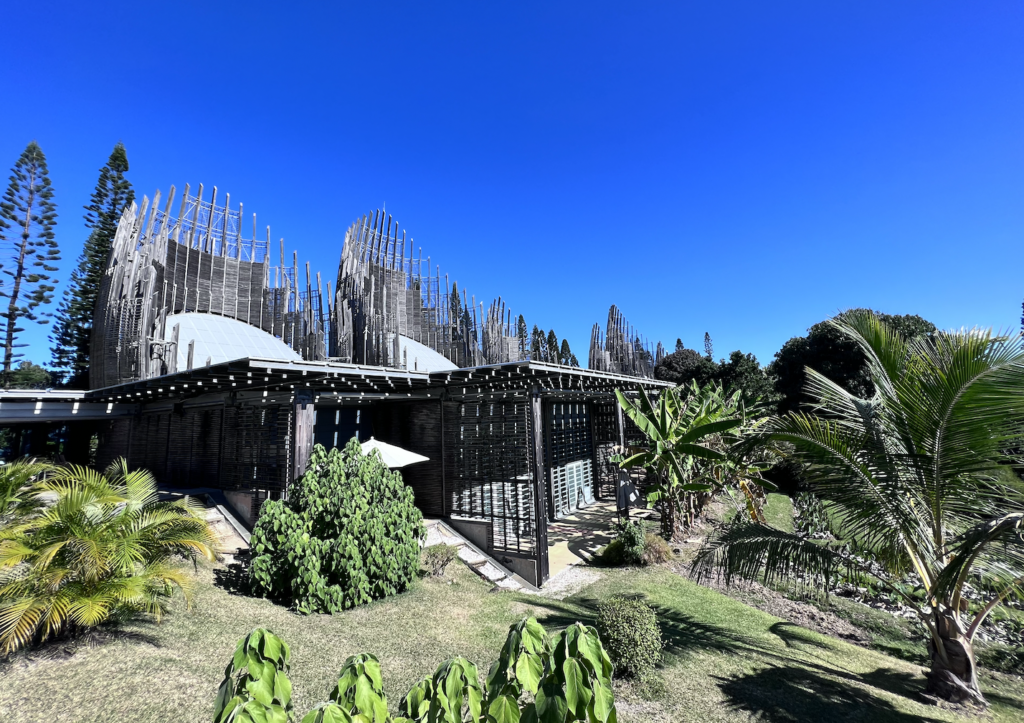

We did a half day trip to Tjibaou Cultural Center which is located in Tinu Peninsula northeast of historic Noumea. Designed by renowned architect Renzo Piano, the center is named after Jean-Marie Tjibaou. It is a large compound consisting of ten conical-shaped structures, inspired by traditional Kanak huts, set in lush subtropical vegetation. The world class museum showcases an impressive collection of Kanak artifacts and contemporary artworks, and a very brief exhibit about Jean Marie Tjibaou and the Kanak history.

Visiting this beautiful museum brought rather mixed emotions and thoughts, and I left feeling bewildered with many questions.

It has been a long time since I’ve visited an architectural masterpiece. We have been in the Pacific islands for over a year now where nature is certainly more interesting and notable than any man made structures. Hence it was a total surprise to find this iconic architectural gem on this small Pacific island. I’ve always admired Renzo Piano’s work and was not disappointed. His design seamlessly blends modern aesthetics with traditional Kanak influences. The center’s ten conical-shaped buildings, reminiscent of traditional Kanak huts, are beautifully crafted with natural wood. Despite the distinctive appearance of the conical structures, the design integrates harmoniously with the lush natural environment. The use of natural light and open spaces create a sense of serenity and connection to nature. As we moved through the building, I was filled with such joy and happiness.

Yet at the same time, something felt amiss and not quite right.

At the entrance gate we received a welcome pamphlet with the map and introduction to the Tjibaou cultural center. I read with great interest to learn more about who Tjibaou was as I have never heard of him before. Yet the entire introduction made no mention of Jean-Marie Tjibaou or the Kanak history, but only about Renzo Piano and the design features of the center, as if the project is a celebration of Renzo Piano’s architectural brilliance.

The main exhibits were extensive about Kanak artefacts, designs and traditions through the ages, yet there was little historical context or background information. There was also a huge room with models and multimedia presentation dedicated to Renzo Piano and the design of the center. Finally at the end of our visit we saw a brief exhibit about Tjibaou and the Kanak contemporary history, yet the information was incomplete and spotty. A few photographs and notes about Jean-Marie Tjiabaou hinted at his assassination, the Kanak oppression by the colonialists and their struggle for indigenous rights and the preservation of their culture. It seems obvious the curators just wanted to get this topic done and over with quickly. It stinks of colonial whitewash.

Another disconcerting thing about the center is the monumental scale and extravagant cost of the facilities. It doesn’t take an architect to know that the construction and maintenance of the center required significant financial resources. On the day when we visited, there was perhaps a dozen other visitors in the vast compound and the center seems out of the place in a tiny country (population 270,000) with not many tourists. Wouldn’t this substantial investment be better utilized to address issues such as poverty, healthcare, and education within the Kanak community?

I left the center feeling uneasy with many more questions than answers. In the evening I did some reading and learnt more about Jean-Marie Tjibaou, the Kanaks and the independence movement, as well the story about the commissioning of the center.

The Kanak people are the indigenous inhabitants of New Caledonia, a French overseas territory in the Pacific. They have a rich history that dates back thousands of years. In the 19th century, French colonization began in New Caledonia. The arrival of European settlers brought significant changes to the Kanak way of life. The Kanak people faced land dispossession, forced labor, and cultural assimilation under French rule. The French claimed the central islands and relegated the indigenous population to smaller reservations at the archipelago’s periphery. These historical injustices led to various resistance movements and conflicts between the Kanak people and the colonial authorities.

Jean-Marie Tjibaou, son of a Kanak chief was a prominent Kanak leader and advocate for indigenous rights and the preservation of Kanak culture. Tjibaou played a central role in leading negotiations, international advocacy, and peaceful protests to raise awareness about the Kanak cause. Tragically Tjibaou was assassinated by a radicalized member of the Kanak community in 1989 who objected to the signing of the Matignon Accords with the French government.

While it was Tjibaou who initiated the idea of the Kanak cultural center, the project was commissioned by Mitterrand and funded by the French government in the wake of Tjibaou’s murder. The government’s motive, at least in part, was to ease social and political tensions between the Kanaks and the French settlers soon after the assassination, which could potentially lead to New Caledonia’s secession and independence from France.

The Kanak independence movement remains active today. 41% of New Caledonia population is Kanak and majority is pro-independence. Since 2018, New Caledonia has held three votes on independence. The first two polls saw an increase of the pro-independence vote from 43.3% in 2018, to 46.7% in 2020. But when the final referendum was called in 2021, pro-independence parties boycotted the vote due to the impact of Covid on the Kanak population. The government went ahead with the vote and the final result showed overwhelming support for New Caledonia to remain in France.

So I learnt all this about Jean-Marie Tjibaou and the Kanak history from google rather than at the center that is named after the man. Isn’t it absurd and ironic?!

Here is a heart breaking quote by Tjibaou that speaks loudly of the pain and suffering of the Kanak people.

“I would say that the hardest thing may not be to die; the hardest thing to do is to stay alive and feel like a stranger in your own land, to feel that your country is dying, to feel powerless to raise high the claim to reconquer the sovereignty of Kanaky.”